Large Vestibular Aqueduct Syndrome

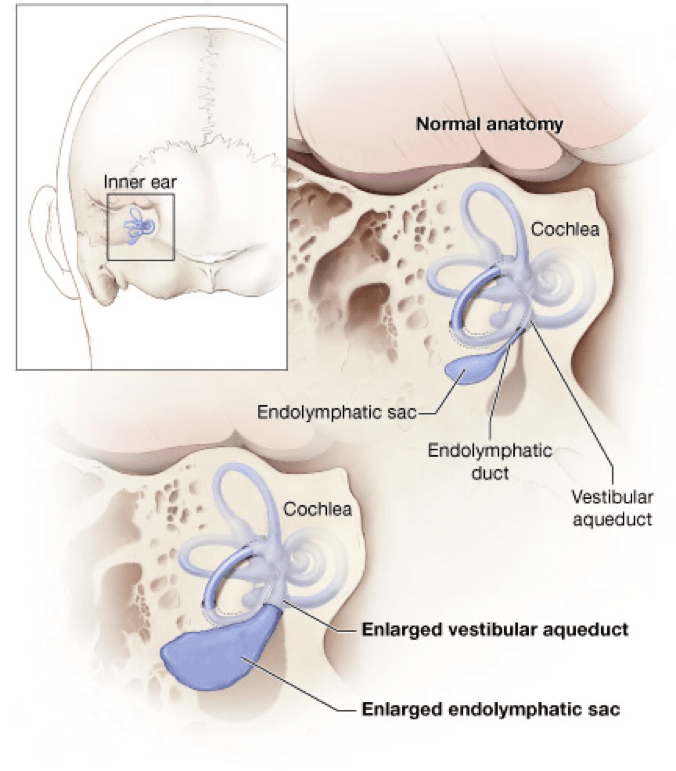

Large vestibular aqueduct syndrome (LVAS), also known as enlarged vestibular aqueduct (EVA) or large endolymphatic sac anomaly (LESA), refers to the presence of congenital sensorineural hearing loss with an enlarged vestibular aqueduct due to enlargement of the endolymphatic duct. It is thought to be one of the most common congenital causes of sensorineural hearing loss. Vestibular aqueducts are narrow, bony canals that travel from the inner ear to deep inside the skull. The aqueducts begin inside the temporal bone, the part of the skull just above the ear. The temporal bone also contains two sensory organs that are part of the inner ear. These organs are the cochlea, which detects sound waves and turns them into nerve signals, and the vestibular labyrinth, which detects movement and gravity. These organs, together with the nerves that send their signals to the brain, work to create normal hearing and balance. Running through each vestibular aqueduct is a fluid-filled tube called the endolymphatic duct, which connects the inner ear to a balloon-shaped structure called the endolymphatic sac.

If a vestibular aqueduct is enlarged, the endolymphatic duct and sac usually grow large too. The functions of the endolymphatic duct and sac are not completely understood. Scientists believe that the endolymphatic duct and sac help to ensure that the fluid in the inner ear contains the correct amounts of certain chemicals called ions. Ions are needed to help start the nerve signals that send sound and balance information to the brain.

Symptoms of LVAS

Although large vestibular aqueducts are a congenital condition, hearing loss may not be present from birth. Age of diagnosis ranges from infancy to adulthood, and symptoms include fluctuating and sometimes progressive sensorineural hearing loss and disequilibrium.

Diagnosis

Due to the variable signs of EVA, diagnosis requires special care and attention to a person’s symptoms and medical history, especially for children. In addition to a complete medical history and physical examination, the diagnostic process for uncovering EVA usually involves audiologic and vestibular testing as well as radiologic assessment. Diagnosis is usually done by positively identifying EVA on a CT scan, or confirming an enlarged endolymphatic duct and sac on high-resolution MRI. Thyroid, renal, and cardiac function may also be analysed, and genetic screening is sometimes also performed.

Historically, medical and surgical treatments have not reversed the progression of hearing or vestibular losses from an EVA. Steroid use for sudden hearing loss associated with EVA has not proven effective. Surgical shunting or removal of the endolymphatic sac is harmful and not considered a treatment option.

There is no cure for EVA, but early diagnosis and prevention from (further) head trauma is necessary. People with EVA are cautioned to avoid contact sports and wear a helmet while bicycling or performing other activities that elevate risk of head injury.

Amplification in the form of hearing aids can be helpful. In the case of fluctuating or progressive hearing loss, hearing aids with flexible programming options are necessary. Cochlear implants have also proven to be beneficial in some patients with EVA (this will depend on the existence of any co-morbid inner ear anomalies). In those persons with related vestibular symptoms, treatment may include vestibular rehabilitation therapy.

Predicting what will ultimately happen in any one case of EVA is difficult because the condition follows no typical course. No relationship exists between how large the aqueduct is and the amount of hearing loss a person may sustain. Some cases progress to profound deafness, some include vestibular losses or difficulties, and other cases lead to neither. It’s important to remember that the signs and symptoms of EVA are quite variable.

Hearing difficulties often manifest in early childhood, but there is no reliable way to predict how much hearing loss will occur or how it will (or will not) progress.

Vestibular symptoms may also appear early, but are much more difficult to identify in the very young.